This experience features audio clips and interactive elements.

Please be sure to have your speakers turned on.

SKIP

SKIP

The advent of effective pharmacological therapy for sexual dysfunction in men has resulted in a better understanding of the importance of sexuality and physical intimacy to quality-of-life (QOL) throughout a man's lifetime, but less attention has been focused on women. Sexual health and a desire for intimacy are equally important issues affecting overall sense of well-being, self-esteem, and relationships for women. Studies have demonstrated that sexual health and health status are inextricably linked,1-4 yet female sexual dysfunction (FSD) remains underdiagnosed and undertreated.

A roundtable attended by a distinguished faculty of 10 multidisciplinary experts in the field of sexual medicine was held in November 2013, to identify gaps in the understanding of hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) that result in its underdiagnosis and undertreatment of HSDD and to establish a Web site that will help bridge those gaps. This interactive publication is based on that discussion. Click on the embedded links to hear audio clips recorded from our discussion, and view the animated figures. Many of the clinical pearls are based on our clinical expertise/experience.

Sincerely,

Co-Chairperson

HerDesire Initiative

Co-Chairperson

HerDesire Initiative

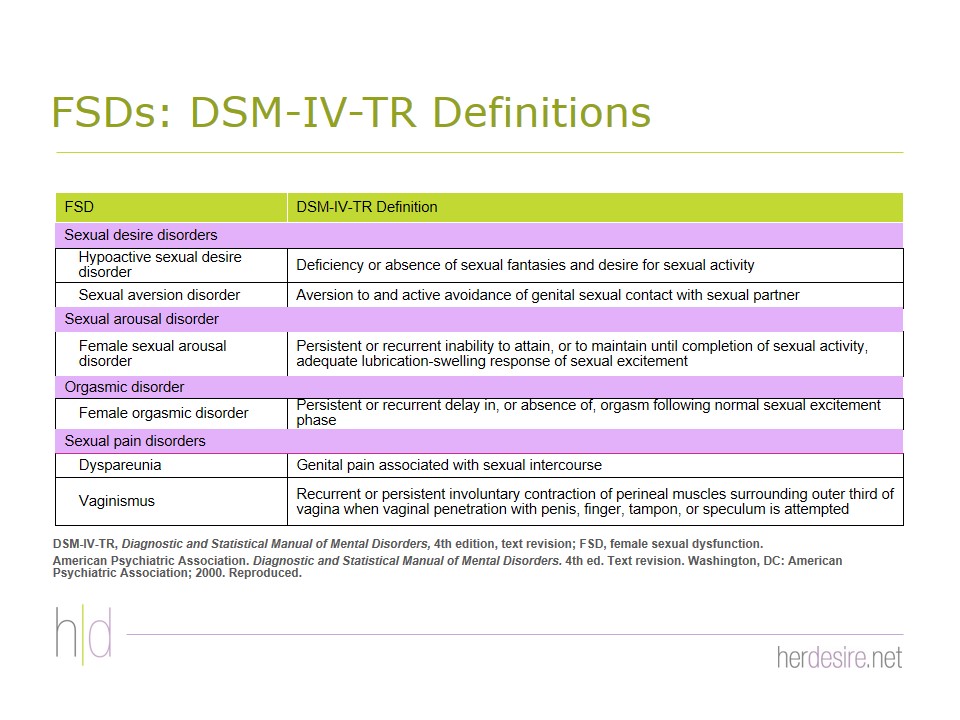

Disorders of female sexual function include sexual arousal disorder, orgasmic disorder, sexual pain disorders, and sexual desire disorders.5 HSDD has generally been defined as the continual or recurring deficiency or absence of sexual fantasies/thoughts and/or desire for or receptivity to sexual activity that causes sexually related emotional and psychological distress and is not caused by a drug or medical condition.2,5-8 Inclusion of sexually related personal distress is an essential element of the definition and a key criterion for diagnosis of HSDD.5,9 Once thought to be a psychiatric disorder, the diagnostic criteria for HSDD are defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association which was not designed to include organic causes of sexual disorders.10

Figures 2 & 3In 2013, the DSM-5 reclassified HSDD and female sexual arousal disorder (FSAD) as a combined female sexual interest/arousal disorder11 Figure 1 in part because women themselves rarely distinguish between desire and arousal as separate entities.12 The DSM-5 specifiers are defined by onset ( ie, lifelong versus acquired), context (ie, generalized versus situational), and severity (ie, mild, moderate, severe). Because this reclassification has been the subject of considerable controversy and debate2,13 and because most of the available data was generated before the reclassification, we will be primarily discussing HSDD according to the DSM-IV definition/classification.

Anita H. Clayton, MD, IF

Anita H. Clayton, MD, IF

HSDD can have a very real negative impact on women's relationships and overall sense of well-being.14 Epidemiologic surveys have shown that low sexual desire is associated with negative effects including poor self-image, mood instability, and depression Figure 4; 4,15 reduced satisfaction with their sex lives Figure 5 and strained relationships with partners4,9,14,15 poor physical and mental health status Figure 6; 4,15 and a reduced health-related (HR) QOL Figure 7.4,14,15 Biddle et al4 found that women with HSDD showed impairment of HRQOL similar to that of adults with other chronic conditions such as diabetes and back pain. Additionally, HSDD is often comorbid with other FSDs Figure 8.14-16 In the Women's International Study of Health and Sexuality (WISHeS), women with very low levels of sexual desire reported having sex but rarely or never initiating sexual activity, achieving orgasm, or masturbating.15

The negative effect of FSD/HSDD is not limited to younger women. While low sexual desire may not be distressing for women without sexual partners, women are sexually active throughout their lifespans Figure 9,17 and FSD can affect and be upsetting for women at any age. The Prevalence of Female Sexual Problems Associated with Distress and Determinants of Treatment Seeking (PRESIDE) study found, for example, that any distressing FSD occurred in about 15% of women aged 45-64 years (HSDD = 12.3%) and in 9% of women age ≥ 65 years (HSDD = 7.4%).18

The negative emotional and psychological factors associated with HSDD may be, in part, both causes and effects of HSDD,2 with interaction among the factors and bidirectional interactions between the factors and HSDD potentially resulting in worsening of both.19,20 Some of the psychosocial and interpersonal factors implicated in contributing to development of HSDD have also been reported as the effects of HSDD.19,20

Estimates of the prevalence of HSDD vary widely depending upon how it was defined and measured.21 Although such methodological inconsistencies make it difficult to compare estimates across studies, sexual desire problems are consistently reported to be the most common FSD among women.21,22 From the National Health and Social Life Survey, 43% of 1,749 women surveyed suffered from FSD, making sexual problems more common in women than in men (31%), and nearly one third of the women surveyed experienced no or reduced sexual interested.14,22 The incidence was generally similar across age groups, making it the most common sexual problem identified by women between the ages of 18 and 59 years. The PRESIDE study found a 9.5% prevalence of low desire with distress among 31,581 US women age ≥ 18 years Figure 10.23,24 After adjusting for concurrent depression, the prevalence of HSDD was 6.3%. WISHeS found that the prevalence of HSDD among women with sexual partners varied by age and menopausal status, ranging from 9% in naturally postmenopausal women to 26% in younger surgically postmenopausal women Figure 11.15

In the PRESIDE study, about 28% of the women with low sexual desire reported the presence of sexually related distress.9 Analysis of this subset of women showed that 64% were premenopausal (age ≤ 55 years) and 81% had a current partner. Without assigning cause or effect, Rosen et al9 found that the strongest independent correlates of sexual distress among these women with HSDD were the presence of a current partner (OR = 4.63, 95% CI = 4.11-5.22) and age. For women who had low sexual desire, the odds of having sexually related distress were highest for women aged 25-34 years (OR = 2.42, 95% CI = 1.80-3.25) and declined progressively with each decade thereafter.9 Shifren et al18 reported that the highest prevalence of any sexual problem with distress occurred among middle-aged women (ages 50-59 years.) Other correlates of distressing sexual problems included poor self-reported health, low education level, depression, anxiety, thyroid conditions, and urinary incontinence.9,18 The healthcare characteristics of women in the PRESIDE study who were identified as having sexual problems (n = 3,239) were also assessed. The vast majority had a primary care provider (PCP), health insurance, prescription coverage, had undergone a routine check-up in the previous year, and were currently using a prescription medication Figure 12.24

Most women do not seek formal healthcare for FSD. In the PRESIDE study, only 35% of women sought any formal healthcare Figure 13.24 Their usual pattern for seeking help from a healthcare provider (HCP) varied widely: most sought formal healthcare only after attempting self-treatment. The PRESIDE study found that, women who sought formal help, the vast majority (~85%) went first to their gynecologists (46.7%) or PCPs (38.5%) Figure 14.24 Most women who sought help for decreased desire with distress did so during a routine physical examination or during an appointment for a medical condition other than a sexual problem Figure 15.24 Only 6% of responders reported making an appointment specifically to discuss a sexual problem.

Reasons that women are reluctant to seek formal healthcare for their sexual problems include embarrassment,24,25 absence of a current partner,24 lack of education on sexual health,25 the fear that the HCP would be uncomfortable, the belief that HCPs are unconcerned about sexual problems and will be dismissive of their sexual concerns,26 and the misconception that there is no medical treatment for the problem Figure 16.26 Some of these beliefs are, unfortunately, based on personal experience. A web-based survey (N = 3,807) showed that many women have had negative experiences when they did seek formal help for their sexual problems Figure 17.27

When asked what they believe are the primary patient-specific barriers to management of sexual dysfunction, PCPs listed patient reluctance/embarrassment, lack of knowledge, and thinking it's "normal" as the primary reasons patients do not seek help for sexual dysfunction Figure 18.28

In a survey of practice patterns conducted by the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) (N = 471), most respondents said they believed that screening for FSD was somewhat or very important (47% and 42%, respectively), yet nearly one fourth of them admitted that they never or rarely did so.29 Clinician barriers to the diagnosis and management of FSD/HSDD include a low priority placed on sexual health; lack of time, training30 and experience; communication skills, and knowledge about therapeutic options25,28,29,31 and fear of "opening the floodgates" if they ask.28 PCPs also mentioned lack of insurance-approved treatments or availability of psychosexual services (24%) and lack of freedom to prescribe (21%).28 In the AUGS survey, 69% of respondents underestimated the prevalence of FSD in their patient population, and 20% said they did not screen because most of their patients were elderly and, therefore, did not need to be screened.29

A pilot study of attitudes about HSDD conducted among residents and faculty at an academic primary care clinic found that most responders had little confidence in their ability to make a diagnosis of or manage HSDD, had not screened for HSDD, and had never prescribed medication for patients with HSDD Figure 19.32 No significant gender differences were observed in this study, but faculty providers did have more confidence than residents in diagnosing and treating HSDD.

David J. Portman, MD, IF, FACOG

David J. Portman, MD, IF, FACOG

Patient gender and age are also factors in the comfort level of physicians in taking a sexual history and in their perceptions of the comfort level of patients.33 In a survey sent to 131 physicians, 69 of 78 responders said they take sexual histories. Both male and female physicians reported being significantly less comfortable assessing the sexual problems of patients of the opposite sex, and male physicians were significantly more likely than female physicians to perceive discomfort in their female patients. Patient characteristics that caused physician discomfort included age (<18 or >65 years), education below college level, and marital status (divorced or single).

Women obtain information about their sexual problems from sources other than their physician, such as leaflets at the HCP office or hospital, friends and relatives, the internet, and health-related books.34 Women between the ages of 18 and 40 years are the most likely to use the internet for obtaining health information. The internet has greatly affected the flow of medical information that was previously fully under the control of HCPs, allowing patients to participate more fully in the management of their health.35 Patients may, for example, come in armed with information about experimental treatments about which the physician was unaware. Patients may find information about side effects of medications and complications of diseases that are more frightening than helpful and may have trouble sorting out the information. False information and testimonials are propagated easily and quickly on the internet. Many patients are unable to distinguish between credible sources and those that are questionable and believe anything that they see in print on the computer screen is factual. The internet makes up-to-date information quickly available and can be extremely helpful for physicians searching for diagnoses or for assessment tools to aid in diagnosis. However, patients do not have the physician's expert background knowledge, and the internet may be a double-edged sword when patients consult the internet in an attempt at self-diagnosis. Sometimes, this may prompt the individual to consult a physician, but often it simply reinforces hypochondria. While Web sites and e-mail can be an efficient way to provide patients with test results, receiving such data out of context may be confusing and worrisome for many patients.35 It might be wise for clinicians to ascertain the sources women have used, caution them about unreliable sources, and counter incorrect information, if necessary.

Credible sources of educational materials for patients are needed so that HCPs may guide their patients to reliable information.34 Similarly, a source of assessment tools and information to help physicians diagnose and treat sexual disorders is badly needed.36

Strategies for asking about sexual function may be general or structured

Figures 20 - 23 37-39 and done in person or by a screening questionnaire. General questions can be open-ended, inquiring about sexual health during routine visits, or use of a screening tool. A brief waiting-room questionnaire, such as the 4-item Sexual Symptom Checklist Figure 2440,41 can be useful in 2 ways: it lets the patient know right away that sexual health is important and appropriate to discuss, and it provides information to the HCP to help direct the discussion. However, some people dislike the anonymity and apparent coldness of the method.42 HCPs should use the communication strategy with which they and their patients are the most comfortable.

A 2-part study including both a population survey and a randomized clinical trial conducted by Sadovsky et al38 found that in-person interviewing (starting with general questions about sexual activity and then becoming more specific) or using a written scale or questionnaire were equally effective. The ubiquity style of question was found to be significantly more effective than direct questions with older women, particularly those more than age 60 years.

Specific techniques to encourage patients to discuss their sexual concerns include using body language that puts the patient at ease; projecting confidence; actively listening with eye contact; using language appropriate to the age, ethnicity, and culture of the patient; and sitting down with the patient in a private setting (eg, an office) after rapport has been established and after the physical examination when the patient is clothed and comfortable (never in an examination gown).42-45 Asking open-ended questions with silences will encourage the patient to speak and open up.39,44

Sharon J. Parish, MD, IF

Sharon J. Parish, MD, IF

Some patients may use terms that clearly indicate distress associated with sexual complaints (eg, angry, frustrated, guilty) but other women may be much more subtle or use euphemisms. Clinicians need to keep a high level of awareness for these clues, particularly when coupled with a known causative or contributory factor.

Susan Kellogg - Spadt, CRNP, PhD, IF, CST

Susan Kellogg - Spadt, CRNP, PhD, IF, CST

When a positive response is obtained, the physician should acknowledge its importance and indicate what the next step will be: more questions, a follow-up appointment, diagnosis and assessment, treatment or referral.36

Sharon J. Parish, MD, IF

Sharon J. Parish, MD, IF

Stanley E. Althof, PhD, IF

Stanley E. Althof, PhD, IF

Sheryl A. Kingsberg, PhD, IF

Sheryl A. Kingsberg, PhD, IF

Irwin Goldstein, MD, IF

Irwin Goldstein, MD, IF

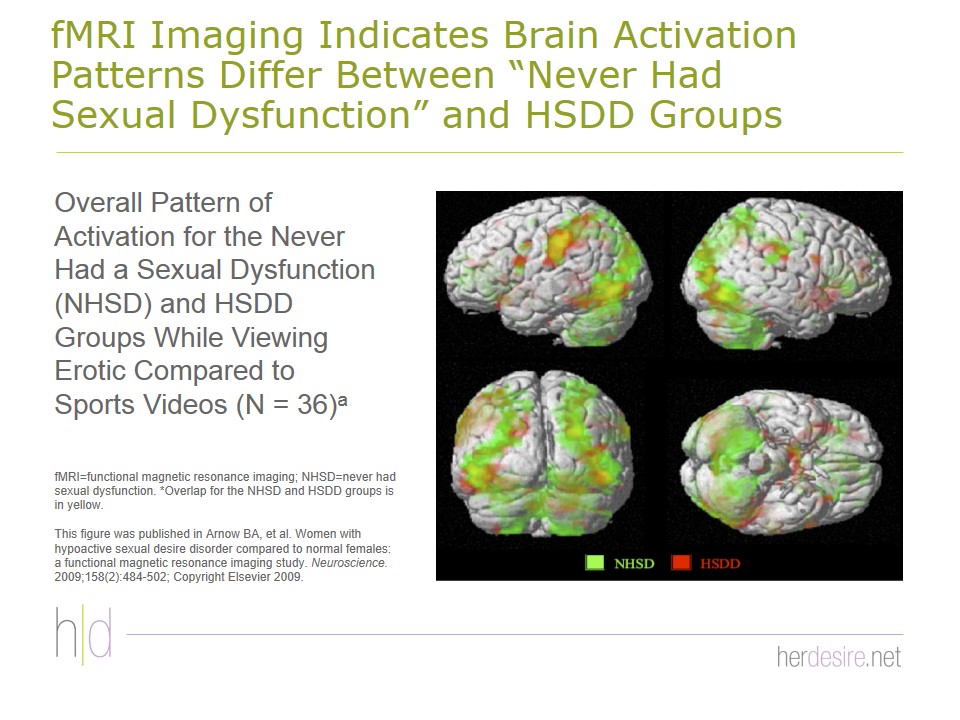

Education about anatomy, aging (if appropriate), and sexual response can be helpful and reassuring to the patient. A number of models of sexual response have been identified including linear and nonlinear models, but many experts now prefer the biopsychosocial model Figure 25.2,46,47 It may be useful to provide some of the recent information about the physiological contribution to sexual dysfunction. New data from functional magnetic resonance imaging studies show that blood flow and activation patterns of limbic and cortical structures in the brain differ between patients who have never had sexual dysfunction and those who have HSDD

Figures 26 - 27.48-50

Irwin Goldstein, MD, IF

Irwin Goldstein, MD, IF

A stepwise diagnostic and treatment algorithm such as the one produced by the Fifth International Consultation for Sexual Medicine (ICSM-5) may be useful, particularly for HCPs who have little experience and/or are still somewhat uncomfortable with management of FSD/HSDD Figure 28.40,51

Questioning patients about their sexual practices is critical, and HCPs have many opportunities during which a discussion of sexual health is appropriate, but it is most appropriate during an annual checkup, particularly during the genitourinary, gynecologic, or obstetric portion of the inquiry, or at a focused visit for genitourinary or gynecologic symptoms.45 It would not be appropriate and very awkward to initiate a discussion of sexual concerns in some situations, during a checkup for completely unrelated symptoms (eg, probable otitis media), for example.

Sharon J. Parish, MD, IF

Sharon J. Parish, MD, IF

Raymond C. Rosen, PhD

Raymond C. Rosen, PhD

David J. Portman, MD, IF, FACOG

David J. Portman, MD, IF, FACOG

Many HCPs wait for patients to bring up the subject. In the Women's Sexual Health Foundation Survey (N = 391), less than 9% of respondents indicated that their provider always initiated questions about sexual difficulties during an annual office visit.52 Only about one in 10 women will bring it up themselves, however, even those who are highly distressed by their sexual problems. Most patients prefer to have the physician initiate the conversation.36 Nearly three fourths of respondents of the Women's Sexual Health Foundation Survey said they would be comfortable talking with their clinician about sexual problems but preferred that their HCP initiate the discussion.52

David J. Portman, MD, IF, FACOG

David J. Portman, MD, IF, FACOG

Sharon J. Parish, MD, IF

Sharon J. Parish, MD, IF

David J. Portman, MD, IF, FACOG

David J. Portman, MD, IF, FACOG

Sharon J. Parish, MD, IF

Sharon J. Parish, MD, IF

Time constraints for even the busiest clinical practice should not be an issue for the initial screening, which need take only a minute or 2 and consist of a couple of questions Figure 29.42 A study of 887 gynecologic outpatients found that only 3% of women spontaneously mentioned any FSD, but, with just 2 questions, an additional 16% of the patients acknowledged a sexual complaint of some kind.53

Normal female sexuality and attitudes about it vary greatly among different individuals and different cultural/ethnic groups, and approximately 40% of women do not, therefore, rate sex as important for their well-being.46 Such women might have low sexual desire but would not be diagnosed with HSDD. Although used primarily as a research tool, the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDS-R) is a validated instrument that may be helpful for some clinicians or, at the very least, suggest questions that will help identify the presence of distress associated with HSDD Figure 30.7 A score of ≥11 diagnoses HSDD; a score ≥15 indicates significant distress.

Michael L. Krychman, MDCM, MPH, IF

Michael L. Krychman, MDCM, MPH, IF

After identification of a sexual complaint, a more thorough evaluation is necessary Figure 31.42 If time is an issue, make a separate appointment to have a more in-depth discussion.36,44

James A. Simon, MD, CCD, NCMP, FACOG, IF

James A. Simon, MD, CCD, NCMP, FACOG, IF

If the complaint is beyond the training or comfort of the HCP, referral to a specialist is in order.42 When referring, it may help to reassure the patient that they are not being abandoned or dismissed, and schedule a follow-up visit in 6 months.36

During the sexual history-taking and subsequent assessments, focused/specific questions should be used rather than the open-ended screening questions.20 Ideally, the sexual health history was incorporated into the general health history.45 If that has not been done, however, the first procedure in management of HSDD is to take a complete sexual history that should include all potential influences on sexual function Figure 32.42,54 The medical information should include both past medical history and current health status and endocrine function, as many medical conditions—including diabetes, androgen insufficiency, estrogen deficiency, and thyroid conditions—can affect sexual function.55 Reproductive formation should include a thorough past history and current status, including sexually transmitted disease, gynecologic pain, and the urinary system. Medication history is important since many drugs can affect sexual function Figure 33.56,57

Clinicians should also assess psychological factors associated with sexual desire/arousal disorders, particularly depression, as well as sexual abuse/emotional neglect in childhood, traumatic experiences during puberty, perceived stress, distraction, self-focused attention, anxiety, personality variables, and body-image self-consciousness.58

Bitzer et al20 have combined the previously described steps into a standardized diagnostic interview Figure 34 that culminates in a 9-field biopsychosocial matrix, which will provide the information necessary to appropriately manage the HSDD. Brotto et al58 also recommends a similar formulation of the diagnoses that integrates all information obtained from the assessment(s) and physical examination.

The differential diagnosis of HSDD is challenging because decreased sexual desire can be affected by many different biomedical and psychosocial factors Figure 35.8 When making a differential diagnosis (exploring the conditioning factors), biomedical and psychiatric factors should be ruled out (or in) first Figure 36.20 This is done with a thorough medical and sexual history and, eventually, a physical examination. A diagnosis of HSDD requires a clinical evaluation that takes into account the various factors that affect sexual functioning.8 A diagnosis of HSDD is not made if the sexual dysfunction is due exclusively to a specified medical or psychiatric condition or substance abuse.

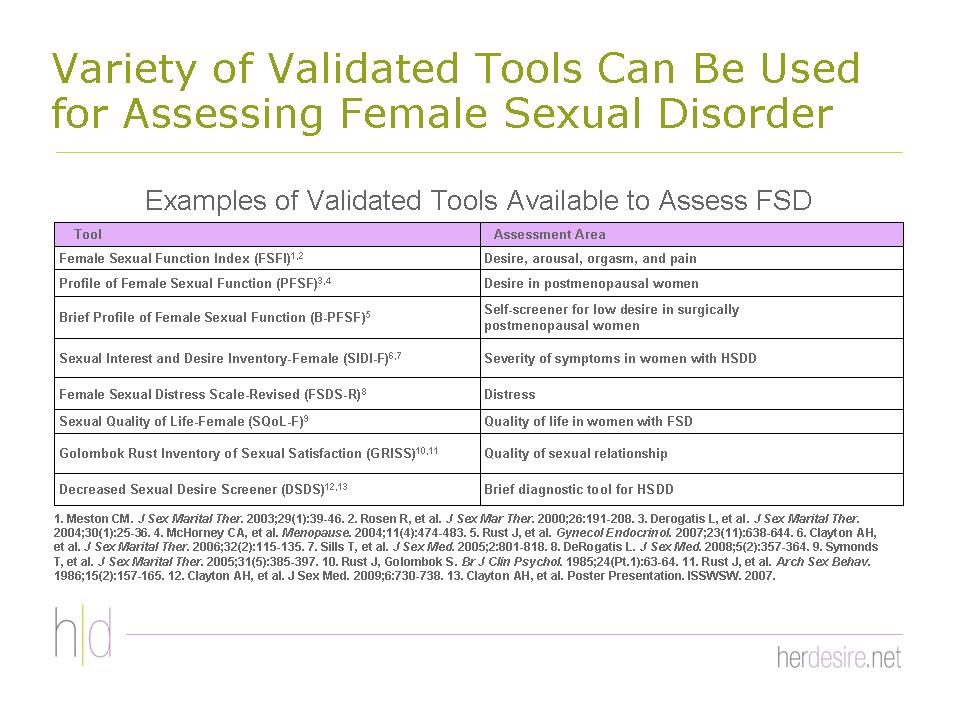

Several psychometric instruments are available that can help diagnose HSDD

Figures 37 - 39.7,59-63 It is important to recognize their uses and limitations. Some, for example, some are most appropriate for clinical trials, while others may specifically diagnose only one type of HSDD (eg, the 5-item Decreased Sexual Desire Screener ) for generalized acquired HSDD) or may have been validated in only one patient population (eg, The Profile of Female Sexual Function for postmenopausal women).

A gynecological examination Figure 40 is recommended to assess and rule out medical/physical contributing factors and is essential for women with secondary HSDD related to endocrine changes or HSDD combined with other dysfunctions, particularly sexual pain.58 Ultrasound is recommended only if a gynecological examination shows an abnormality.19,58 Routine laboratory testing is unlikely to identify causes of sexual dysfunction but may be necessary to rule out medical conditions that are known to play a role in HSDD.19,40,58 Diagnostic assays are recommended for women with symptoms or signs of thyroid disease or hyperprolactinemia (galactorrhea, irregular menses, and/or infertility). The psychosocial aspects of aging and menopause are more important factors than hormones, and hormonal measurements need be made only if medically warranted for some other condition.58 Testosterone plays a role in women's sexual response, but testosterone levels should not be used for diagnosis because serum androgen levels do not correlate with HSDD.2

What the goals of treatment should be is currently a hotly debated topic. Many goals of treatment can be return of desire, increased satisfaction with overall sex life, return of or improved emotional and physical intimacy, improved self-esteem/self image, improved relationship with partner, stabilized mood, and improved overall HRQOL. On one side is the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which specifies that the number of satisfying sexual events is the primary endpoint for clinical trials; on the other side are experts in the field who understand that counting events is too simplistic an endpoint for FSDs, which are very complex, and does not reflect clinical reality.56,64 Woman may have sex for reasons (eg, relationship issues) other than sexual desire.10

Raymond C. Rosen, PhD

Raymond C. Rosen, PhD

Physiological genital responses may occur in women with HSDD even when subjective sexual interest/arousal is low or absent, and women generally have other goals.8,47,65 The goals for each individual may vary depending upon how the HSDD affected that patient (eg, what negative feelings that patient expressed). Women place more importance on overall sexual satisfaction, which has both personal and relationship domains, and the level of sexual satisfaction depends largely on expectations and past experience.58 More research is needed on the definition and correlates of sexual satisfaction in women and in how they differ from those for men.58

Clinicians who prefer objective assessments of treatment success may wish to use the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI).36

Sexual dysfunction is a common complaint in many medical conditions, particularly urologic disorders.66 The steps in an appropriate process-of-care management strategy for HSDD Figure 41 are first to address modifiable risk factors and treat any underlying conditions, including a partner's sexual dysfunction, which can negatively affect a woman's sexual desire.58,67 Since mental and physical exhaustion related to daily activities can be a contributing factor in lack of desire, clinicians should always emphasize the importance of a healthy lifestyle, exercise, and rest.68

Types of interventions include psychological/psychosocial therapy, physical therapy, and pharmacologic therapies, as well as adjunctive and alternative therapies.7,69 Nonpharmacologic approaches also might include bibliotherapy using credible sources, and sex toys and lubricants if and as appropriate.

Psychological/psychotherapeutic interventions can have sustained improvements over time and may be used alone or combined with pharmacotherapy. Most often, psychological interventions are targeted to both the woman and her partner. Treating only the woman's symptoms may cause problems in a relationship.36 Additionally, if the relationship is a precipitating or maintaining factor, treating only the woman is unlikely to succeed.

Some clinical evidence suggests some effectiveness for group cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based CBT, sensate focus and other traditional sex therapy techniques (Evidence Level: Grade C).58 While traditional sex therapy is only modestly effective, mindfulness-based CBT has shown promise for sexual desire problems.2 Randomized controlled clinical trials of psychological therapy for HSDD in women are urgently needed.58

Only one medication, flibanserin, has yet been approved specifically for treating HSDD, and the search for additional, effective therapies continues. Many agents have been investigated Figure 42:

- Estrogen therapy—Clinical studies support the use of local low-dose, but not systemic, estrogen therapy for select urogenital complaints, including dyspareunia secondary to vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), which may improve associated sexual disorders.70 Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has increased sexual thoughts and interest as well as sexual activity compared with no HRT, but whether the effect was direct or indirect (via improvement in vaginal dryness) is not known. Local low-dose estrogen therapy is safe and does not cause significant proliferation of the endometrium or serum estrogen levels. Tibolone, an orally administered synthetic steroid that produces estrogen, progestin, and androgen effects, is widely used in other countries for menopausal symptoms, is well tolerated, and improves sexual desire and reverses vaginal atrophy71 but has not been approved in the United States, probably due to fear resulting from the findings of the Women's Health Initiative about serious adverse effects.72 A recent randomized, controlled clinical trial involving 140 postmenopausal women showed significant improvements in desire as well as arousal and orgasmic domains of the FSFI.73

- Ospemifene—is a selective estrogen receptor modulator indicated for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and VVA.74,75 Relief of dyspareunia reduces pain with sexual activity,74 and a study reported at the Endocrine Society's Annual Meeting in San Francisco, June 2013, reported significant improvement in all 6 domains of sexual function, including desire, as measured by the FSFI among 919 women taking ospemifene for dyspareunia.76,77

- Topical alprostadil—a prostaglandin that causes vasodilatory responses in men that is effective for sexual arousal disorder, has had mixed results in women.71 A multicenter, randomized placebo-controlled trial dose-ranging study involving 400 women with FSAD showed significantly improved FSFI scores in the arousal, orgasm, and satisfaction domain at all dose levels tested. Significant improvements in desire domain (FSFI) and distress (FSDS) occurred at the highest dose level (900 μg).78 Topical formulations of alprostadil are in clinical trials.71

- PDE5-I—The phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor (PDE5-I), sildenafil, has not demonstrated any benefit in treating primary HSDD,2,79 but a small trial showed significant reduction in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI)-associated sexual dysfunction.80

- Testosterone—Testosterone can be administered as a transdermal patch, cream, gel, or, in some specialized centers, implant.71 The transdermal testosterone patch (TTP) therapy has been found to be effective for naturally menopausal women with normal estrogen levels and marginally effective for premenopausal women. The data are conflicting for testosterone in estrogen-depleted women. The long-term risks of testosterone are unknown. (Evidence Level: Grade B)58 Therapy with TTP has been associated with increased hair growth (but not acne, alopecia, or voice change) and application site reactions.2,71 Two-year cardiovascular, breast, and endometrial safety data for the TTP in postmenopausal women have been reassuring, but long-term safety trials are needed.71 Testosterone gel showed early promise, but 2 Phase III randomized controlled trials did not show a benefit over placebo.2,71 Testosterone undecanoate has not been well studied but cannot be recommended at this time because of undesirable physiological peaks of circulating testosterone in a pharmacokinetic trial. Off-label use of testosterone injections and transdermal testosterone formulated for men is common, but they result in inappropriately high testosterone levels and should not be prescribed for women.71

- Testosterone in combination with other agents—Based on the hypothesis that HSDD could be due either to a relative insensitivity to sexual cues or to enhanced activity of sexual inhibitor mechanisms, 2 formulations of testosterone, one with a PDE5-I inhibitor (vardenafil) and the other with a 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor agonist (5-HT1Ara, buspirone) are being tested:81

- Testosterone + a PDE5-I. Results of a pilot study showed promise in a randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial of 56 women with HSDD or FSAD, significantly improving both physiological and subjective measures of sexual functioning compared with placebo, including sexual desire, arousal, and overall sexual functioning and satisfaction in low-sensitivity women.12 Women who have searched the internet may be familiar with this agent under the name 'Lybridos'.

- Testosterone + 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor agonist (5-HT1Ara, buspirone) showed a marked improvement in sexual function compared with placebo in high-inhibition women.82 Women who have searched the internet may be familiar with this agent under the name 'Lybrido'.

- Bremelanotide—is a melanocortin receptor-4 agonist derived from the Melanotan 2 Peptide that was being tested as a sunless tanning agent when unexpected sexual side effects (sexual arousal and spontaneous erections) were reported by 90% of the male volunteer test subjects.83 Development of a bremelanotide nasal spray for treating sexual dysfunction was discontinued in 2007-2008 due to adverse effects on blood pressure.2,69 It has been reformulated as a subcutaneous injection and is currently being evaluated. In Phase 2 trials, the agent, called PT-141, has demonstrated benefit in improving sexual desire and arousal disorder in postmenopausal women2 and increased desire and arousal and reduced stress in premenopausal women with HSDD and FSAD84,85 and is currently in Phase 3 trials. Other melanocortin receptor agonists are also being evaluated.69

- Centrally acting agents—Centrally acting agents show promise, but more randomized, controlled trials and safety evaluations are needed. Evidence Level: Grade A.58

- Bupropion is not an investigational drug, nor is it indicated for treating sexual dysfunction, but it is often used to treat the sexual side effects of SSRIs.2 Bupropion is an antidepressant that, in nondepressed women with HSDD, blocks the uptake of norepinephrine and dopamine and was been found effective in arousal and orgasmic, but not desire, disorders.58 In women with mixed sexual symptoms associated with SSRIs, adding bupropion significantly increased self-reported desire and sexual activity.

- Flibanserin (Addyi) is as an orally administered, nonhormonal drug that increases dopamine and norepinephrine (a sexual excitatory factor) while decreasing serotonin (a sexual inhibitor factor) Figure 43.2,86 Three phase 3 pivotal trials evaluating flibanserin in premenopausal women have been completed.2,87-89 In the pivotal BEGONIA trial involving 1,087 premenopausal women, flibanserin significantly increased the frequency of SSEs, significantly improved total and desire domain scores on the FSFI, and significantly reduced sexually-related distress on the FSDS-R.87 The most common adverse events were somnolence, dizziness, nausea. Data have been accumulated from over 11,000 women to date.2 Flibanserin is FDA-approved to treat HSDD in women who have not gone through menopause, who have not had problems with low sexual desire in the past, and who have low sexual desire no matter the type of sexual activity, the situation, or the sexual partner; their HSDD is not due to a medical or mental health problem, problems in the relationship, medicine or other drug use (please see full Prescribing Information).

- Nutraceuticals—Figure 44. Many patients take over-the-counter (OTC) herbs, botanicals, and supplements for their problem. Clinicians should be aware of what types of complementary medicine their patients may be using, but patients will seldom volunteer this information.69,71,91,92 ArginMax (L-arginine combined with supplements). L-arginine is known to be a precursor of nitric oxide. One small study showed increased desire in pre-, peri-, and postmenopausal women, but this agent should be considered investigational at this time.71,91 Patients should be advised to use only reliable sources for such products.

- Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is a pro-hormone of testosterone available OTC as a supplement. Clinical trials have generally shown no benefit of oral DHEA for FSDs in postmenopausal women.71 However, a proof of concept study of daily vaginal transdermal DHEA in 216 postmenopausal women showed significant improvement in desire and vaginal dryness, as well as arousal and orgasm after 12 weeks of treatment.2,71,93 Clinical efficacy trials of transdermal vaginal DHEA are under way.

The best and most effective treatments will be multidimensional and multidisciplinary, combining psychological/psychosocial therapies with medical interventions.20,47 Medical therapies may be highly effective for many sexual dysfunctions, but without addressing the larger biopsychosocial issues, treatment fails because patients often discontinue the medical therapy.47,71 The literature suggests a synergistic benefit from using combined treatment modalities. There is a need to identify effective treatment modalities and integrated management strategies for FSD/HSDD.47

Due to the multifactorial etiopathologies of FSDs, including HSDD, accurate diagnosis and optimal management of FSDs, including HSDD, require a multimodal and multidisciplinary approach that may involve specialists such as urogynecolgists, urologists, gynecologists, advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, sexologists, psychologists, and physical therapists in addition to PCPs.8,66

HCPs need to view sexual health as an important concern, but medical students and practicing physicians in the US report being underprepared to address their patients' sexual health needs.28,30,94 Experts across disciplines, including PCPs, urogynecologists,29 obstetric/gynecologists,95 nurse practitioners and physician assistants,96 agree that medical education in sexual health has been inadequate.30 Sexual health education, when it exists at all, is often elective, reinforcing the opinion of medical students that sexual health is less important.94 Coverage of certain sexual health topics—those involving older age groups, youth, and disabled individuals—is particularly inadequate.

Comprehensive multidisciplinary, cross-disciplinary education is needed.25,31,94 In 2010 the education committee of the International Society for Sexual Medicine recommended a set of objectives in attitudes, knowledge, and skills for HCPs Figure 45. More recently, a summit held in December, 2012, brought together sexual health educators in the US and Canada as well as representatives from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Medical Association, and the Association of American Medical Colleges—all of whom who have a strong interest in advancing sexual health education for HCPs—to recommend strategies for improvement Figure 46.94

FSD is common and has a significant negative impact on a woman's physical and mental health and QOL. HSDD is the most common FSD, affecting approximately one in 10 American women, both young and elderly, pre- and perimenopausal. Multiple factors may affect sexual function in women across the life cycle.

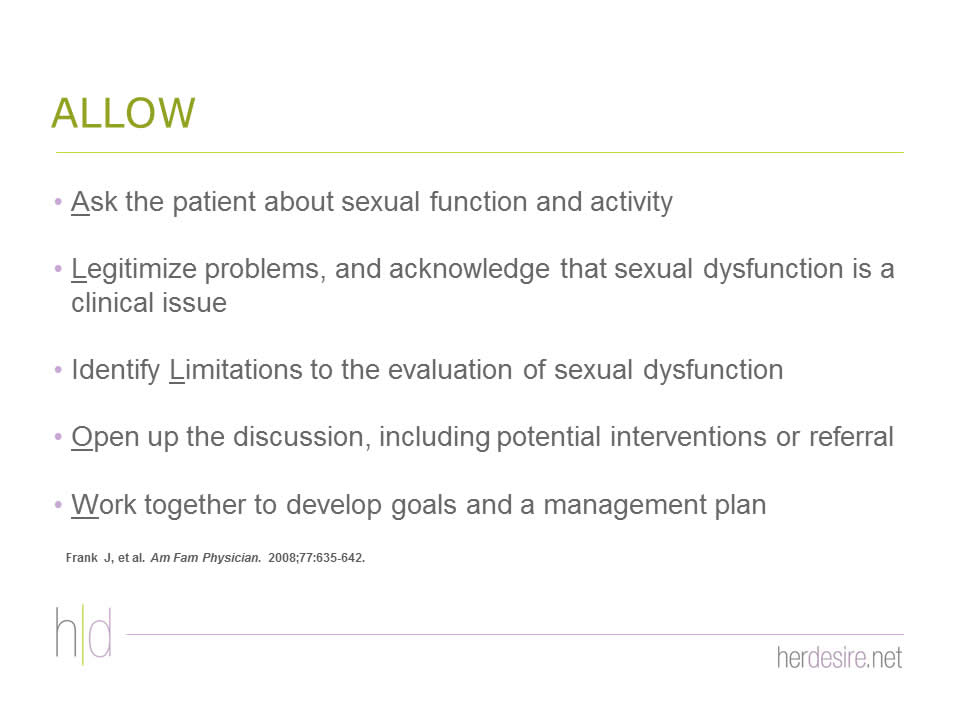

Patients want to discuss their sexual concerns, but prefer for their HCP to initiate the discussion. Physicians should identify a communication strategy and make a commitment to use it. Open-ended questions work best for initial discussions. Validated questionnaire or structured interview techniques such as ALLOW or PLISSIT can be helpful for HCPs that are inexperienced in managing sexual complaints. Both nonpharmacological and pharmacological interventions have demonstrated benefits for women with HSDD.

- Lochlainn MN, Kenny RA. Sexual activity and aging. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8):565-572.

- Kingsberg SA, Rezaee RL. Hypoactive sexual desire in women. Menopause. 2013;20(12):1284-1300.

- Sobczak J. Female sexual dysfunction: knowledge development and practice implications. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2009;45(3):161-172.

- Biddle AK, West SL, D'Aloisio AA, Wheeler SB, Borisov NN, Thorp J. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women: quality of life and health burden. Value in Health. 2009;12(5):763-772.

- Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, et al. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: definitions and classifications. J Urology. 2000;163(3):888-893.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 1994.

- Derogatis L, Clayton A, Lewis-D'Agostino D, Wunderlich G, Fu Y. Validation of the female sexual distress scale-revised for assessing distress in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2008;5(2):357-364.

- Simon JA. Low sexual desire--is it all in her head? Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Postgrad Med. 2010;122(6):128-136.

- Rosen RC, Shifren JL, Monz BU, Odom DM, Russo PA, Johannes CB. Correlates of sexually related personal distress in women with low sexual desire. J Sex Med. 2009;6(6):1549-1560.

- Segraves R, Woodard T. Female hypoactive sexual desire disorder: History and current status. J Sex Med. 2006;3(3):408-418.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Poels S, Bloemers J, van Rooij K, et al. Toward personalized sexual medicine (part 2): testosterone combined with a PDE5 inhibitor increases sexual satisfaction in women with HSDD and FSAD, and a low sensitive system for sexual cues. J Sex Med. 2013;10(3):810-823.

- Clayton AH, DeRogatis LR, Rosen RC, Pyke R. Intended or unintended consequences? The likely implications of raising the bar for sexual dysfunction diagnosis in the proposed DSM-V revisions: 1. For women with incomplete loss of desire or sexual receptivity. J Sex Med. 2012;9(8):2027-2039.

- Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281(6):537-544.

- Leiblum S, Koochaki PE, Rodenberg CA, Barton IP, Rosen RC. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women: US results from the Women's International Study of Health and Sexuality (WISHeS). Menopause. 2006;13(1):46-56.

- Hartmann U, Heiser K, Rűffer-Hesse, Kloth G. Female sexual desire disorders: subtypes, classification, personality factors and new directions for treatment. World J Urol. 2002;20(2):79-88.

- Patel D, Gillespie B, Foxman B. Sexual behavior of older women. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30(3):216-220.

- Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, Segreti A, Johannes CB. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):970-978.

- Bitzer J, Giraldi A, Pfaus J. Sexual desire and hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. Introduction and overview. Standard operating procedure (SOP Part 1). J Sex Med. 2013;10(1):36-49.

- Bitzer J, Giraldi A, Pfaus J. A standardized diagnostic interview for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women: standard operating procedure (SOP Part 2). J Sex Med. 2013;10(1):50-57.

- McCabe MP, Goldhammer DL. Prevalence of women's sexual desire problems: what criteria do we use? Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42(6):1073-1078.

- Laumann EO, Glasser DB, Neves RCS, Moreira ED Jr. for the GSSAB Investigators' Group. A population-based survey of sexual activity, sexual problems and associated help-seeking behavior patterns in mature adults in the United States of America. Int J Impot Res. 2009;21(3):171-178.

- Johannes CB, Clayton AH, Odom DM, et al. Distressing sexual problems in United States women revisited: prevalence after accounting for depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(12):1698-1706.

- Shifren JL, Johannes CB, Monz BU, Russo PA, Bennett L, Rosen R. Help-seeking behavior of women with self-reported distressing sexual problems. J Women's Health. 2009;18(4):461-468.

- Kingsberg SA. Identifying HSDD in the family medicine setting. J Fam Pract. 2009;58(7 Suppl Hypoactive):S22-S25.

- Marwick C. Survey says patients expect little physician help on sex. JAMA. 1999;281(23):2173.

- Berman L, Berman J, Felder S, et al. Seeking help for sexual function complaints: what gynecologists need to know about the female patient's experience. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(3):572-576.

- Humphery S, Nazareth I. GPs' views on their management of sexual dysfunction. Fam Pract. 2001;18(5):516-518.

- Pauls RN, Kleeman SD, Segal JL, Silva WA, Goldenhar LM, Karram MM. Practice patterns of physician members of the American Urogynecologic Society regarding female sexual dysfunction: results of a national survey. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16(6):460-467.

- Solursh DS, Ernst JL, Lewis RW, et al. The human sexuality education of physicians in North American medical schools. Int J Impot Res. 2003;15(suppl 5):S41-S45.

- Abdolrasulnia M, Shewchuk RM, Roepke N, et al. Management of female sexual problems: perceived barriers, practice patterns, and confidence among primary care physicians and gynecologists. J Sex Med. 2010;7(7):2499-2508.

- Harsh V, McGarvey EL, Clayton AH. Physician attitudes regarding hypoactive sexual disorder in a primary care clinic: a pilot study. J Sex Med. 2008;5(3):640-645.

- Burd ID, Nevadunsky N, Bachmann G. Impact of physician gender on sexual history taking in a multispecialty practice. J Sex Med. 2006;3(2):194-200.

- Neelapala P, Duvvi SK, Kumar G, Kumar BN. Do gynaecology outpatients use the Internet to seek health information? A questionnaire survey. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(2):300-304.

- Hartzband P, Groopman J. Untangling the Web—patients, doctors, and the Internet. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(12):1063-1066.

- Distinguished Faculty. Needs Assessment Roundtable; Washington, DC: November 17, 2013.

- Frank JE, Mistretta P, Will J. Diagnosis and treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(5):635-642.

- Sadovsky R, Alam W, Enecilla M, Cosiquien R, Tipu O, Etheridge-Otey J. Sexual problems among a specific population of minority women aged 40-80 years attending a primary care practice. J Sex Med. 2006;3(5):795-803.

- American Reproductive Health Professionals (ARHP). Algorithms for Screening and Treating FSD. https://www.arhp.org/files/kellogg_algorithm.pdf. Accessed February 2014.

- Hatzichristou D, Rosen RC, Derogatis LR, et al. Recommendations for the clinical evaluation of men and women with sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1 Pt 2):337-348.

- Hatzichristou D, Rosen RC, Broderick G, et al. Clinical evaluation and management strategy for sexual dysfunction in men and women. J Sex Med. 2004;1(1):49-57.

- Kingsberg SA. Taking a sexual history. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33(4):535-547.

- Buster JE. Managing female sexual dysfunction. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(4):905-915.

- Tomlinson J. ABC of sexual health: taking a sexual history. BMJ. 1998;317:1573–1576.

- Peck SA. The importance of the sexual health history in the primary care setting. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2001;30(3):269-274.

- Rosen RC, Barsky JL. Normal sexual response in women. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2006;33(4):515-526.

- Althof SE, Leiblum SR, Chevret-Measson M, et al. Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2005;(2)793-800.

- Arnow BA, Millheiser L, Garrett M, et al. Women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder compared to normal females: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroscience. 2009;158(2):484-502.

- Woodard TL, Nowak NT, Balon R, Tancer M, Diamond MP. Brain activation patterns in women with acquired hypoactive sexual desire disorder and women with normal sexual function: a cross-sectional pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(4):1068-1076. Epub 2013 Jul 2.

- Bianchi-Demicheli F, Cojan Y, Waber L, Recordon N, Vuileumier P, Ortigue S. Neural bases of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women: an event-related FMRI study. J Sex Med. 2011;8(9):2546-2559.

- Althof SE, Rosen RC, Perelman MA, Rubio-Aurioles E. Standard operating procedures for taking a sexual history. J Sex Med. 2013;10(1):26-35.

- Martinez L. The Women's Sexual Health Foundation.https://www.womenshealthresearch.org/site/DocServer/DC_briefing_HSDD_and_FSD_10-_2009_st.pdf?docID=2944 Accessed January 16, 2014.

- Bachmann GA, Leiblum SR, Grill J. Brief sexual inquiry in gynecologic practice. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73(3 Pt 1):425-427.

- Meston C. Aging and sexuality. In: Successful Aging. West J Med. 1997;167(4):285-290.

- Basson R, Schultz WW. Sexual sequelae of general medical disorders. Lancet. 2007;369(9559):409-424.

- Clayton AH, Dennerstein L, Fisher WA, Kingsberg SA, Perelman MA, Pyke RE. Standards for clinical trials in sexual dysfunction in women: research designs and outcomes assessment. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1 Pt 2):541-560.

- Kingsberg SA, Janata JW. Female sexual disorders: assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. Urol Clin North Am. 2007;34(4):497-506, v-vi.

- Brotto LA, Bitzer J, Laan E, Leiblum S, Luria M. Women's sexual desire and arousal disorders. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1 Pt 2):586-614.

- Clayton AH, Goldfischer ER, Goldstein I, Derogatis L, Lewis-D'Agostino DJ, Pyke R. Validation of the decreased sexual desire screener (DSDS): a brief diagnostic instrument for generalized acquired female hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). J Sex Med. 2009;6(3):730-738.

- Meston CM. Derogatis LR. Validated instruments for assessing female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(Suppl 1):155-164.

- Arrington R. Cofrancesco J. Wu AW. Questionnaires to measure sexual quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(10):1643-1658.

- Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191-208.

- Isidori AM. Pozza C. Esposito K, et al. Development and validation of a 6-item version of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) as a diagnostic tool for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2010;7(3):1139-1146.

- Kingsberg SA, Althof SE. Satisfying sexual events as outcome measures in clinical trial of female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2011;8(12):3262-3270.

- Segraves RT. Management of hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Adv Psychosom Med. 2008;29:33-32.

- Wehbe SA, Whitmore K, Kellogg-Spadt S. Urogenital complaints and female sexual dysfunction (part 1). J Sex Med. 2010;7(5):1704-1713.

- Goldstein I. Current management strategies of the postmenopausal patient with sexual health problems. J Sex Med. 2007;4(Suppl 3):235-253.

- Walton B, Thorton T. Female sexual dysfunction. Curr Womens Health Rep. 2003;3(4):319-326.

- Simon JA. Opportunities for intervention in HSDD. J Fam Pract. 2009;58(7 Suppl Hypoactive):S26-S30.

- Nappi RE, Davis SR. The use of hormone therapy for the maintenance of urogynecological and sexual health post WHI. Climacteric. 2012;15(3):267-274.

- Fooladi E, Davis SR. An update on the pharmacological management of female sexual dysfunction. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(15):2131-2142.

- Robb-Nicholson C. What's the latest on tibolone, the estrogen alternative? Harvard Women's Health Watch; April 2004. Reprinted in By the Way, Doctor. Harvard Health Publications, Harvard Medical Schools. https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsweek/Whats_the_latest_on_tibolone.htm. Accessed January 1, 2014.

- Ziaei S, Moghasemi M, Faghihzadeh S. Comparative effects of conventional hormone replacement therapy and tibolone on climacteric symptoms and sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2010;13(2):147-156.

- Portman DJ, Bachmann GA, Simon JA; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2013;20(6):623-630.

- Osphena (ospemifene) tablets, for oral use. Full Prescribing Information. Bethesda, MD:Shionogi Inc.; 2013.

- Constantine JJ, Giliberti M, Graham S. Ospemifine significantly improves female sexual dysfunction as measured by the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): Results of a randomized placebo controlled trial. Poster presented at ENDO June 15-18, 2013. Abstract. https://endo.confex.com/endo/2013endo/webprogram/Paper9611.html. Accessed February 15, 2014.

- Harding A. Ospemifene pill improves several measures of sexual function. The Doctor's Channel. https://www.thedoctorschannel.com/view/ospemifene-pill-improves-several-measures-of-sexual-function/. Accessed February 15, 2014.

- Liao Q, Zhang M, Geng L, et al. Efficacy and safety of alprostadil cream for the treatment of female sexual arousal disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in chinese population. J Sex Med. 2008;5(8):1923-1931.

- Berman JR, Berman LA, Toler SM, Gill J, Haughie S; Sildenafil Study Group. Safety and efficacy of sildenafil citrate for the treatment of female sexual arousal disorder: a double-blind, placebo controlled study. J Urol. 2003;170(6 Pt 1):2333-2338.

- Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, Croft HA, Debattista C, Paine S. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300(4):395-404.

- Bloemers J, van Rooij K, Poels S, et al. Toward personalized sexual medicine (part 1): integrating the "dual control model" into differential drug treatments for hypoactive sexual desire disorder and female sexual arousal disorder. J Sex Med. 2013;10(3):791-809. Epub 2012 Nov 6.

- van Rooij K, Poels S, Bloemers J, et al. Toward personalized sexual medicine (part 3): testosterone combined with a Serotonin1A receptor agonist increases sexual satisfaction in women with HSDD and FSAD, and dysfunctional activation of sexual inhibitory mechanisms. J Sex Med. 2013;10(3):824-37. Epub 2012 Nov 6.

- Peptide Sciences. PT-141 10mg (Bremelanotide 10 mg). https://www.peptidesciences.com/pt-141. Accessed January 15, 2014.

- Jordan R, Edelson J, Greenberg S, et al. Efficacy of subcutaneous bremelanotied self-administered at home by premenopausal women with female sexual dysfunction: a placebo-controlled dose-ranging study. Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health (ISSWSH). New Orleans, LA; February 28-March 3, 2013. https://www.palatin.com/products/bremelanotide.asp. Accessed January 16, 2014.

- Palatin Technologies. Bremelanotide for Sexual Dysfunction. https://www.palatin.com/products/bremelanotide.asp. Accessed January 16, 2014.

- Clayton AH, Hamilton DV. Female sexual dysfunction. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33(2):323-338.

- Katz M, DeRogatis LR, Ackerman R, et al; BEGONIA trial investigators. Efficacy of flibanserin in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: results from the BEGONIA trial. J Sex Med. 2013;10(7):1807-1815.

- Derogatis LR, Komer L, Katz M, et al. Treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women: efficacy of flibanserin in the VIOLET study. J Sex Med 2012;9:1074-1085.

- Thorp J, Simon J, Dattani D, et al. Treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women: efficacy of flibanserin in the DAISY study. J Sex Med 2012;9(3):793-804.

- Sprout Pharmaceuticals. Sprout Pharmaceuticals receives clear guidance from FDA on path forward to resubmit New Drug Application for fibanserin, the first potential medical treatment forh sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women. Raleigh, NC. https://www.fiercebiotech.com/press-releases/sprout-pharmaceuticals-receives-clear-guidance-fda-path-forward-resubmit-ne. Accessed January 15, 2014.

- Ito TY, Polan ML, Whipple B, Trant AS. The enhancement of female sexual function with ArginMax, a nutritional supplement, among women differing in menopausal status. J Sex Marital Ther. 2006;32(5):369-378.

- Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. About Herbs, Botanicals & Other Products. https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/integrative-medicine/about-herbs-botanicals-other-products. Accessed February 1, 2014

- Labrie F, Archer D, Bouchard C, et al. Effect of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (Prasterone) on libido and sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2009;16(5):923-931.

- Coleman E, Elders J, Satcher D, et al. Summit on medical school education in sexual health: report of an expert consultation. J Sex Med. 2013;10(4):924-938.

- Pancholy AB, Goldenhar L, Fellner AN, Crisp C, Kleeman S, Pauls R. Resident education and training in female sexuality: results of a national survey. J Sex Med. 2011;8(2):361-366.

- Mansell D, Salinas GD, Sanchez A, Abdolrasulnia M. Attitudes toward management of decreased sexual desire in premenopausal women: a national survey of nurse practitioners and physician assistants. J Allied Health. 2011;40(2):64-71.